“Wake up.” When Crazy Me rests a hand on my forehead, it jolts me from sleep. “It’s raccoons.”

“What?” I shiver out of a very pleasant dream of licking frosting off Amisha’s nose. “Get!” I flail at him in the darkness and thump his shoulder.

“Raccoons! With their masks and their tiny black hands and their fleas. Rooting through our garbage.”

“What time is it?” I lift my head off the pillow to look at the clock. “Great, it’s four twenty-three.”

“Do you know how many raccoons there are?” he asks. As usual, my irritation bounces off him. “They’re everywhere, like furry cockroaches. I have no doubt whatsoever. The next pandemic will be huge—raccoon flu.”

“What, the last one wasn’t bad enough for you?” I press the pillow to my ears. The room is hot; the AC has shut itself off again.

He has to tell me about all of the ailments raccoons are subject to: congestive heart failure, cancer, hepatitis, distemper, rabies, the common cold. They get more diseases than any other wild animal. Crazy Me has been googling them since I went to bed. The pathology of the intestinal raccoon roundworm baylisascaris procyonis is particularly nasty. The eggs are sticky and pretty much invulnerable and if they get into an aberrant host, which is anything not a raccoon, like us, the larvae get confused and wander around the body compromising the liver, eyes, brain, spinal cord, or other organs.

“Roundworms aren’t the flu,” I say.

“I know that,” says Crazy Me. “But this paper from the Centers for Disease Control says there are all kinds of influenza receptors in raccoon tissues. A blood survey found twenty-five percent of the raccoons in Wyoming had flu exposure. Look at the data for 2014; raccoon flu can easily make the jump to humans. It’s only a matter of time.”

I switch on the bedside light. We blink at each other and then I scan the printout he thrusts at me. “So what are we supposed to do?”

“Hoard surgical masks?” he says. “Drink pricier Scotch? Maybe buy AstraZeneca stock?” He yawns. “Anyway, I just thought you’d want to know. I’m tired now, so I’m going to bed.”

This is how it’s been recently. Crazy Me sketches some doomsday scenario in the middle of the night and then retreats to the garage. Me, I lose another night’s sleep.

#

I head to the kitchen, stand in front of the open fridge to let the cool pour over me as I drink grapefruit juice out of the carton, then open my laptop on the kitchen table. AstraZenica closed at 39.45 yesterday, down from its fifty-two week high of 51.13. Most market analysts have it as a hold, but its MedImmune subsidiary makes FluMist®, the only nasal spray flu vaccine approved in the U.S. I put in an order for three hundred shares through Schwab for when the market opens.

Crazy Me is crazy, but he has his moments of prescience. He started one of the very first blogs on Blogger and just a year later called the dot-com bust. He discovered Sudoku in Dell Pencil Puzzles and Word Games back in 1989, long before it left for Japan and returned as the Godzilla of brainteasers. We got into Pfizer while Lipitor and Viagra were in clinical trials and bought six acres here on Ledge Lake a year before the bypass opened. But he was wrong about SARS and the Kindle and the Venezuelan war.

And he is crazy.

#

I’ve been up for almost five hours before I see my first patient and I’m dragging as I scan the schedule of morning eye exams. The day after a Crazy Me surprise party can seem to stretch for years—decades—but I have a solo practice, so there’s no help. It’s just me and Shannon the receptionist and my two technicians, Ronnie and Amisha, in the office. Sometimes I feel as if I’m in three places at once. Four, if you count whatever Crazy Me is doing while I’m at the office.

Axel Jensen is in the yellow room. He’s the contractor who used to date my ex-wife, but that’s not anything we can chat about.

“Just put your chin on the rest.” I’m giving him the slit lamp exam; he leans forward. “So, keeping busy?”

“Don’t ask.” He sets his forehead against the support pad. “Had to lay off one of my best carpenters last week. I’m down to three.” He puffs his lips in disgust. “You?”

“Oh, you know. People have to see.” I flick the switch of the Zeiss and a beam of intense blue light illuminates his eyes. “Look up.” I check for surface abrasions and tears. “Left. Down. Right.” I remember that Axel came in two years ago with a half-millimeter splinter of metal lodged in his left eye. He’s fine now, except for the unmistakable flicker of fear I’m seeing in most of my patients these days. “You look just great today, Axel. Cornea, iris, lens, sclera, all great. You’re wearing safety glasses on the job?”

“Ever since the accident.”

“Great, great. So, is business picking up anytime soon?”

“Nah. There are raccoons busier than we are. Renovation work and damn little of that. Everybody’s scared shitless about where things are going. Pardon my French.”

“Tell me about it,” I say.

Inez Ramos is waiting in the blue room. I’ve got upwards of four thousand patients and they all expect me to remember them so I check her chart, which reminds me that she’s sixty-three and a longtime patient. I did cataract surgery on her a year ago—looked then like a good outcome. Basic phacoemulsification. Here’s a note that says she has a diamond the size of a raisin. It’s coming back to me now; her ring is a lethal weapon when she waves her hands. And it says that she’s a quilter. I don’t know from quilts, but if she’s who I think she is, chitchat won’t be a problem. She can talk the shirt off a statue.

I knock. “Good morning, Inez.” I glide into the room. “Great to see you again.”

She looks up from her sewing. “There you are, Doctor Takumi.” She slips a needle into a patchwork of red and white fabric stretched across a wooden hoop. “I’ve just been thinking as I’ve been sitting here about how you changed my life. All the things I see now, everything is so clear, the colors keep getting brighter and brighter.”

“That’s great, Inez.” I twist my mouth into a smile and remember how moments like this used to lift me. “Nice to hear some good news for a change.”

She beams at me and then leans over in the exam chair to put her sewing into a tote.

“Is that one of your quilts?”

She straightens up and holds it for me to admire. “I pieced this block yesterday and got most of it quilted while I was in your waiting room.”

I take the hoop from her. The design looks like the view through a chintz kaleidoscope. “Great. It’s great.” The red swatches remind me of the curtains Grandma Takumi had in the kitchen when she lived in Vermont.

“It’s all hand sewn. The pattern is called Storm at Sea. It’s for my granddaughter. My boy’s little girl. They moved down to Pensacola to get away from all the riots. Her name is Viviana. It means ‘lively’ and that fits her. That child can run rings around rabbits.”

I check her IOL; the lens looks fine, no posterior opacification. Her Optomap pictures show her retina is healthy.

“You’re looking just great, Inez. You’ve got the vision of a woman half your age.”

She rubs her eyelids with her middle fingers. “What about the maculate?”

“Maculate? You mean macular degeneration?”

“My friend Babbsie Huppertz said that when you put that new ILO thingy into my eye, it could make the maculate degeneration.” She unbuttons the bottom button of her cardigan sweater and then rebuttons it. “She had that happen to a friend of hers. So she looked it up on the internet. I don’t bother with all that computer stuff anymore.”

“The intraocular lens is just a bit of plastic.” I rest a hand on her shoulder to reassure her. “It doesn’t cause anything; there have been all kinds of studies. But here.” I swing the Optomap screen toward her so she can see her pictures. “These are your retinas. They’re all nice and pink, you can see blood vessels and the optic disk. That faint dark spot, that’s your macula. If you had degeneration you’d see yellow or maybe red blotches. There and there. Do you see any blotches, Inez?”

She bites her lower lip. “That’s what Babbsie said.”

I turn the screen off. “You know, maybe she was misinformed. We’ve done something like 65 million cataract surgeries. They’re safe as money in the bank.”

She gives me a questioning glance.

I shrug. “So to speak.” I open the door to the room. “There’s just a lot of bad information out there, Inez, on the internet especially. A lot of fear.” She takes the hint and gets off the exam chair. “But I’m glad you asked.” I usher her into the hall. “We’ll see you in six months. By then you should have that quilt finished, yes?”

Alex Dampier is a first time patient. He’s five and, according to the mom, sits too close to the family TV, doesn’t like to be outdoors and says he can’t see his friend Zach when he’s coming down the street. He is dark and squirmy and wears jean shorts and a blue tee shirt with the Superman logo.

“I don’t like it.” He shies away from the phoropter. He can barely read the 20/50 line on the Snellen chart; he needs glasses. “It has too many eyes.” He lifts his feet up as if to push the instrument away. “Looks like a monster.”

“He’s been seeing monsters everywhere recently,” says the mom, whose name I have already forgotten.

The kid slumps in the exam chair. “I don’t want glasses.”

“They’ll make you look cool,” says the mom. “Cool guys wear glasses. Daddy wears glasses.”

“I don’t want to be cool.”

“Superman wears glasses,” she says.

“No, Clark Kent wears glasses,” he replies. “Not Superman.”

“But that’s how he catches monsters,” I say. “Superman does.”

They both stare at me.

“The thing is,” I say, “monsters won’t show themselves when Superman is around. They’re too scared of him. But when he’s Clark Kent, they don’t know that he’s really Superman so they come out and he can spot them because he is wearing glasses. So then he changes into Superman.”

I wink at the mom; Alex is rapt. “So what this machine does,” I swing the phoroptor a couple of inches closer to him, then stop, “is to give you super vision. You’ll be able to see things just like Superman.”

“Monsters?” says Alex.

“If there are any, sure. But as you see, I have super vision too.” I tap the temple of my glasses. “I’ve been looking out for them and I haven’t seen any in a long time, Alex. But I’m ready if they ever should come around here.”

#

It’s such an old and clichéd story, doctors and their nurses, that I am almost ashamed that it has become mine. Amisha Murkarjee came to me from Clearwater Vision Center, a four-doctor practice downtown that closed a year ago last January. She’s a certified RN in ophthalmology. We worked together for nearly seventeen months before anything happened between us. She has curly black hair that hides her tiny ears. She’s two inches taller than I am. She likes to be kissed at the base of her neck just above the collar bone and is ticklish behind the knees. She wears pastel scrub tops in different patterns: ferns and tropical fish and ladybugs and Betty Boop. I asked her once and it turned out she had no idea that Betty Boop was an old-time cartoon character.

We’ve been together now for three weeks and I haven’t yet told her the whole truth about Crazy Me. She knows there is a Crazy Me, but she thinks he’s me. She’s under the impression that sometimes the devil gets into Dr. Ken Takumi, DO. Or maybe a bit too much Glenlivet. Or something. She believes that he’s the me I give permission to do all the stuff I otherwise wouldn’t do.

If only it were that simple.

It would cause trouble at work if Amisha and I were to admit that we were sleeping together. I’m sure that Ronnie and Shannon have figured it out, but as long as we don’t announce our affair, they don’t have to acknowledge it. I suppose pretending things aren’t happening is a kind of hypocrisy, but there’s a lot of that going around. So even if she spends the night at my house or I stay with her, we come and go to the office in separate cars.

I head home to change after the long day and park near the front door. Crazy Me has nested in the garage; I’ve abandoned it to him. The mail is uninspiring: bills, the Journal of Refractive Surgery, and a Netflix. Crazy Me has ordered Bambi. He’s been on a Disney binge lately, says following the news makes him nostalgic. He wishes he was a kid again, living in a saner, safer world. Me too. As I pass the door into the garage I can hear the theme music to The Daily Show. Crazy Me only watches TV on his computer. I slip his DVD across the threshold.

I’m supposed to pick Amisha up for dinner but I have time for a quick power nap. I set the alarm clock for 5:45 and kick my shoes off.

#

Amisha has decided to educate me about beer. “Ben’s Stout,” she says, finishing the pour. She sets the bottle down in front of me, then picks up her own glass, which is already full. “It’s from that new brewery in Salem.” There is a picture of Ben Franklin on the bottle’s label and beneath it the slogan Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.

I consider telling her that studies show consumption of half a liter of beer a day increases risk of bowel and liver cancer by twenty percent, but I don’t want her to know that the poor Deluded Me she thinks she’s with is still snoozing back at our house.

“Hold it up to the light,” she says.

I do, and across the restaurant the waitress nods, mistaking the gesture for a summons. “It’s dark.”

“Yes it is,” Amisha says. “You could view a total eclipse of the sun through this beer. And look at that head. You leave it alone and it’ll still be standing tall at closing.”

“But why would we do that?” I offer my glass to her and we clink.

When she sips her beer it leaves a little foam mustache on her upper lip. Her tongue darts out to wipe it away. She catches me watching her and grins. “What?” she says, her voice low in her throat. “You want some of this?” She licks her bottom lip.

“Absolutely.”

The waitress arrives and she is too eager by half. Business is slow for a Thursday night; there are just two other couples in the place. This suits me fine; people make me nervous, which is why I don’t get out much. I order the Jambalaya Pasta and Amisha gets the Garlic Rubbed Pork Tenderloin.

“So what do you taste?” she says. “Describe it for me.”

“I don’t know.” I hadn’t realized that she was so crazy about beer. “It’s kind of bitter. And thick. No—rich.” I click my tongue against the roof of my mouth. “There’s something… malt?”

“Definitely.” She nods. “I get a little bit of smoke and some oats. It’s an oatmeal stout, of course. And a note of vanilla.”

“Wow.” I salute her. “You have great taste buds. Among other things.”

“I like beer,” she says. “And I like you. Especially since you don’t know much about beer.”

I raise a hand in protest. Beer is four percent alcohol, six percent unfermented carbohydrates, a half percent protein, a half percent ash and eighty-nine percent water.

“Okay, okay.” She cocks her head to one side and fixes me with an appraising stare. “You’ve bought your share of sixes in your day. Bud, Miller—Michelob, if you’re splurging. Am I right?”

“Actually, I like Corona. Más cerveza, por favor.”

We drink to that. “You know what bugs me?” She runs a finger around the rim of her glass. “Beer commercials. They all assume that women don’t like beer.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Because the women never get to drink anything! The truck drivers are slugging down cool ones, the fishermen, the quarterbacks, the goddamn cowboys and the women are serving it to them or ogling them or lying on towels working on their tans. What is it with beer commercials and the beach?”

I have never heard her rant before. “That’s where the bikinis are?” I like it; passion is thin on the ground in the garage.

“It’s not good. I read somewhere that we’re a quarter of the market. Give me just one commercial in four, that’s all I ask. One in ten!” She notices that I’m smiling at her and shakes her head. “Yikes,” she says. “Where did all that come from?”

“I don’t know, but it’s kind of sexy.”

“It’s just that they’re all accessories, you know. Waitresses. Girlfriends. Bimbos.” She reaches across the table and flicks her middle finger against the meat of my hand, as if I’m not paying attention. “I am not an accessory, Doctor.”

#

How crazy is Crazy Me? That’s a matter of disagreement between the two of us. If you consult the DSM-IV-TR, you would have to say that he has bipolar symptoms with regular hypomanic and dysthymic mood swings. He has mild agoraphobia, which is actually something of a relief. I don’t approve of him leaving the house, pretending to be me, although it happens. I’m lucky, I guess, that he’s mostly content to hang around the garage looking at his websites, worrying about asteroids or antibiotic-resistant bacteria or the thirty point drop in the Consumer Confidence Index. And then of course there is dissociative identity disorder, except that he actually is my multiple personality. It’s just that he has a body all his own to play with.

For all that, he copes. His computer monitor is his window on the world. He has a Facebook page and still posts to his blog, Kafka’s Laugh Track. He shows flashes of genuine insight into the people we know and he did come up with those shrewd investments. He’s the reason I was able to pay off my student loans four years early. I’ve seen him maintain a façade of normality for days at a time.

Given that the country is in crisis, he argues, I’m the one who is maladjusted. He likes to call me Deluded Me.

#

After dinner we decide to cruise back to Amisha’s house. The heat of the day has passed so we roll the windows down. We’re listening to Miles Davis’s sultry trumpet work on Birth of the Cool when Amisha sits upright and then leans out her window.

“You all right?” I say.

“Fire,” she says. “Smell it?”

“No,” I say, but then I do.

“Pull over.”

We’re still rolling when she pops out of the car onto the sidewalk. She turns slowly beside the open door as the car dings at her. “Take a left.” She swings back to her seat. “I think it’s down near the park.”

“Is this a good idea?” I say.

“If these are the end times, we can grab a front row seat.” Her smile is so bright that it’s scary.

In the late nineteenth century, Grandview Street was one of the most coveted addresses in town. The mansions opposite Lovell Park were built as monuments to the style and wealth of the Gilded Age. In the middle of the twentieth century, the park became disreputable and the wealthy packed up their Lincolns and Caddys and removed to country estates. One by one the great houses were carved up into shabby apartments. Now the neighborhood needed a shave and a haircut.

129 Grandview might once have been a jewel of Queen Anne style architecture. Its asymmetrical façade is dominated by a brooding gable cantilevered over a rotten porch. The front door and the windows on the first floor are boarded up. Its fish-scale shingles had been green back in the Reagan Administration; now they are the color of bile.

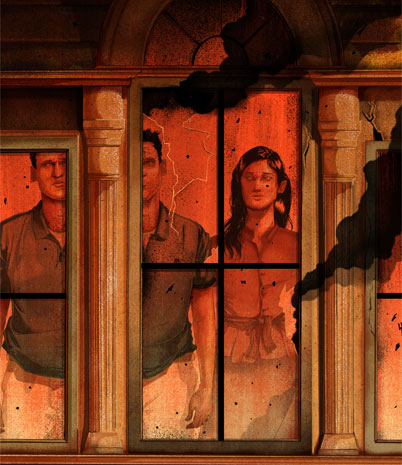

The fire is on the second floor of the abandoned mansion’s octagonal tower. Through a dirty Palladian window I can see tongues of flame licking at the interior. A clump of six or seven people gawks at an old lady in a flowered housedress, who has stretched a garden hose from next door. The good neighbor sprays the tower but the water just splashes against the window and cascades down the shingles.

“I’ve never seen a house on fire before,” says Amisha as she drags me toward the group.

“Where’s the fire department?” I ask.

“We called ten minutes ago,” one of the onlookers says.

As the fire climbs to the third story of the tower I begin to make out my companions. Their faces are rapt in the golden light, their bodies are shadows.

“That hose isn’t doing any good,” someone says. Maybe me; it’s certainly what I’m thinking.

A kid breaks away from us, runs up to the old woman and yells at her. She shakes her head. He stoops to pick up a rock and sets himself close to the house.

“Don’t.” The man is standing right next to me and his shout slaps me in the ear. “You’ll let it breathe.”

Too late. When the kid heaves the rock, the entire window blows out with a crash. He thrusts hands over his head to shield himself as he dances through a shower of glass.

“My god,” cries Amisha. “What was that?” Her arm circles my waist.

I hear a gluey laugh to my right. “That window must have been pretty damn hot.”

Smoke billows through the jagged hole. “I read online somewhere that a house fire can reach 1100 degrees Fahrenheit,” I say, and pull Amisha back several steps. Everybody in our group follows.

“Where’s the fire department?” asks a new arrival.

“They called ten minutes ago,” says Amisha.

“Fifteen,” someone corrects her.

The kid yanks the hose away from the old lady and redirects its thin stream of water, which disappears uselessly into the burning tower. He might as well try pissing on the fire. More and more flames peek through the smoke; the shingles directly above the broken window are scorching.

By the time the fire department pumper arrives, 129 Grandview is fully involved in flame. Maybe a dozen fire chasers have swarmed from around town to witness the spectacle. Firefighters herd us back to the far side of Grandview as the first water cannons begin to rain onto flames flapping like flags on the roof. The old lady who’d lost her hose is huddled on a lawn chair a few feet away. She is wrapped in a pink blanket and is humming tunelessly. Her tears catch the light.

Amisha giggles. “It’s a jack-o’-lantern, the house.” She points. “Fire eyes. And the mouth.” She sways and I steady her with an arm around her waist. She devours the burning mansion with her eyes; her blouse is riding up slightly and I can feel a ribbon of hot skin above the elastic of her slacks. She presses a hand to my chest in her excitement. She hasn’t had that much to drink; I think it must be the fire that has intoxicated her.

Now the windows on the third floor of the house begin to weep as well. Drips of melting flame fall on the overgrown yews planted along the foundation. With a whoosh that sounds like the night breaking, the roof collapses and flings a galaxy of sparks into the sky.

People clap.

She starts when my pinkie slips inside her waistband. “Hey.”

“What?” I murmur. This isn’t about the house anymore; now the fire is on our cheeks.

“Is this what I think it is?” she asks.

“Rome is burning.” Two, three fingers now, stretching. “Let’s fiddle.” I want to nuzzle the glisten of sweat on her upper lip.

“Here?”

I push a kiss onto her ear and whisper. “It’s dark in the park.”

Of course, this is a ridiculous and dangerous idea, but I am crazy with lust. I’ve been too long in the garage so I guide her down Grandview; three houses in we cut across a wild lawn and skirt a lost fence. The lot backs up to a mixed stand of hemlock and white pine. The park is dark but the fire throws enough light that I can see to kick away the fallen branches that block our way.

I unbutton her blouse and tug the straps of her bra down her arms. She yanks my polo shirt over my head and flings it over her shoulder.

“Um… I’m going to need that back eventually,” I say.

“Eventually can wait, Doctor.” She licks beneath my eye.

My zipper is down. I’m kissing her breasts. My shorts are around my ankles. This is something Deluded Me would never do.

She giggles. “What if somebody sees us?”

“Then we’ll charge admission.”

I’m on my knees. My face is between her legs. Then I let myself ease backwards. She’s on top of me. There is so much clamor from the fire. Part of me is with her but another part hears the screech of sirens, the bleat of horns, the sputter of police radios and the crunch of the dying house. But when she breathes into my mouth, there is no past to regret, no future to fear.

When we are finished, she rests on top of me and laughs. I can feel her laughter in my chest. It’s catching.

“Is this you or Crazy Ken?” she says.

“You can’t tell the difference?” I have to be careful here. “Great.”

“Crazy Ken is funnier.” She wriggles her hips. “You’re sexier.”

Someone up at 129 Grandview is shouting. “Lower, low.” It’s darker here than it was a few minutes ago. Maybe they have the fire under control. I’m wondering if I’m going to be able to find my shirt.

I hear something moving close by and to the left. A twig snaps, leaves rustle. “What was that?” I spread my fingers across her naked buttocks as if that might preserve her decency.

“Squirrels,” she says. “Or raccoons.” She props herself up and peers into the night. “Or wolves—grrrr.”

“We don’t have wolves here.”

“No,” she says. “At least, not yet.”

#

I got my B.S. in Biology from Ohio State and graduated magna cum laude from med school at the University of Cincinnati. I interned at Pennsylvania Presbyterian in Philadelphia and did my residency in ophthalmology at the University of Michigan’s W.K. Kellogg Eye Center. I am a doctor of medicine—a scientist. How do I explain what is happening here?

It is hopeless. But it’s not only me. The whole world seems to be flying apart.

#

“…Accuweather forecast calls for a hazy, hot, and humid day with highs this afternoon approaching the upper nineties.”

I reach across the bed, swat at the clock radio and miss. The weight of too much sleep skews my aim.

“Today’s Air Quality Index is expected to reach unhealthy levels, which has led the EPA to issue an advisory calling for people at risk to limit outdoor activities and refrain from strenuous…”

The next time I kill it. I raise my head to peer at the LED on the clock’s face; it reads 5:45. Something is wrong. The numbers go blurry; I blink in the darkness. 5:45 a.m.

Great. I have slept—what? Thirteen hours? Amisha will be furious; I’ve missed our date. She already thinks I take her for granted. I stumble to the bathroom, piss, wash my face, and brush my teeth. On my way to the kitchen, I check the answering machine in the front hall, dreading Amisha’s message.

The light is steady. Unblinking. Just to be sure, I hit play. “You have no new messages.”

Here’s a mystery that will have to wait for coffee. The time may be out of joint, but I have to keep my priorities straight.

While the coffee is brewing, I cross to the door to the garage.

“Hey.” I knock. “You in there?”

No answer.

I open the door. His space is dark except for the bright blue eye of the computer screen. I flick the light switch.

We have a single bay garage with no windows. It can be unbearable in the summer so he leaves the overhead door open a crack to let in air. The walls are sheet rock that I’d had taped and mudded but never bothered to paint; the floor is bare cement. There isn’t room for much furniture: a blue queen-sized futon that folds into a couch during the day, three filing cabinets crammed with who knows what craziness, a chest of drawers that used to be in our Grandpa Takumi’s bedroom at the cottage in Vermont, shelves filled with books that we’ll probably never read again. It’s all gathered around the oriental rug that we inherited from our ex-mother-in-law, Susan. Off to one side is the red formica kitchen table with steel trim that we bought at the yard sale down the street. There’s an open pizza box; crusts are scattered across the tabletop. Never eat the crispy edges of a slice; they look like too much like dog biscuits.

“Hello?” I take the three steps from the house down to the garage. There’s nobody here. The drumbeat in my chest is making me dizzy so I drop onto the chair in front of the computer. I must have jiggled the mouse because the angelfish in the aquarium screen saver freeze and then I’m looking at our Facebook page.

Our profile picture is of us standing on our dock with Ledge Lake in the background. We’re not smiling exactly, but we seem to be amused. I can’t remember who took that picture, him or me.

I discover that now we have 452 friends. I don’t pay much attention to Facebook, that’s his thing. Even though he tells me what he does while I’m gone, it’s all mist and murmurs. I’m supposed to remember his hobbies when I forget what I had for lunch yesterday or which patients I saw last week? As I scroll down the list, I realize that I know hardly any of our new friends. Who is Lurinda Lawrence, for example? George Drozen? Is that where he is now? Out with Cindy Orczowski, whoever she is?

No. I know exactly where he is. I just don’t want to think about it.

Idly I click the Inbox to remind myself what all our friends are saying to us. We get a lot of invitations to Greenpeace events. Several dozen people sent private messages for our birthday in May. And then I spot the note from Michele Haverney, only the face in the profile picture isn’t that of our Michele from 1984. It’s a woman our age, gray and pinched and disappointed. She writes:

An ophthalmologist, oh my! That means you’re a doctor, right? I get confused between ophthalmologist and optometrist. I know that optician is the guy who sells you the glasses. So what are you looking for after all these years, Dr. Ken Takumi? What do you see?

But our Michele is fourteen and she is sitting next to us on a picnic table over on the other side of Ledge Lake at the state park campground and we’ve got Madonna claiming she’s like a virgin on the boombox and why not? Anything was possible back then. No one can see us but the chipmunks. It’s the freshman class picnic and it’s sunny and the breeze carries the warm promise of summer. We don’t know yet that Michele will be moving to Idaho in September. We’ve been wanting to kiss her since the march to Lincoln Square on Earth Day and there is not much time because soon a chaperone will come looking for us. She turns her face up toward us and closes her eyes and we can see the color rising in her pale cheeks and the lock of auburn hair that has strayed across her forehead and, no, we don’t want to close our eyes, we want to see it all so we can return to this moment forever, our first true love, and so I do kiss her but at the same time I am watching myself brush my lips against hers and down the side of her face and we are astounded at just how sweet life used to be.

There’s a crunching behind the futon.

“Hello?”

Silence.

“Someone there?”

A black nose, then beady eyes set in a bandit’s mask. The raccoon sticks its head out and assesses the situation. Then it emerges from behind the couch, snout brushing the floor and the cushion and the wall, as if it is surprised by the scent of its surroundings.

“Hey.”

It steps sideways and then goes up on its haunches, forepaws dangling. It glances around the room and then at its escape route beneath the garage door. It doesn’t seem particularly afraid.

“Get.”

The raccoon drops onto all fours again.

“Get out.”

It ambles behind the futon with an odd humping gait, then comes back out with a pizza crust in its mouth.

“Scoot!”

It considers for a moment and then scurries across the floor under the door and into the uncertain dawn.

© Copyright 2011 by James Patrick Kelly